Introduction

I’ll never forget the morning I discovered a perfectly arranged dead mouse on my bathroom mat, positioned with what seemed like deliberate care, as if my cat Whiskers had spent time ensuring maximum visibility for his “gift.” My initial horror quickly turned to curiosity: why cats bring dead mice home became a question I couldn’t stop thinking about as I gingerly disposed of my unwanted present.

If you’ve experienced the dubious honor of receiving deceased rodents, birds, or other small creatures from your feline companion, you’re far from alone. Studies indicate that outdoor cats bring prey home in approximately 25% of successful hunts, with some particularly dedicated hunters delivering multiple “gifts” weekly to their bewildered humans. This behavior transcends geography, culture, and cat breed—it’s a universal feline phenomenon that has puzzled and sometimes disgusted cat parents throughout history.

Understanding cat hunting behavior requires looking beyond our human tendency to interpret actions through our emotional lens. What seems like a macabre gift-giving ritual to us represents something entirely different to cats—a complex behavior rooted in millions of years of evolutionary programming that domestication has barely touched.

Feline predatory instincts remain remarkably intact despite approximately 10,000 years of living alongside humans. Unlike dogs, whose behavior and even physical form have been dramatically altered through selective breeding, cats remain essentially wild hunters wearing a domestic disguise. The same neural pathways, instincts, and motivations that drove their wild ancestors to hunt for survival continue to operate in the pampered house cat who has never missed a meal.

Cats catching mice and bringing them home isn’t about sustenance—it’s about satisfying one of the most fundamental drives encoded in feline DNA. This behavior serves multiple purposes in the cat’s world, from social bonding and teaching to territory management and pure entertainment. What looks like a disturbing habit from our perspective represents your cat’s attempt to include you in their natural behavioral repertoire.

In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll uncover five fascinating reasons cats engage in this prey-bringing behavior, examine the evolutionary biology that makes hunting irresistible to cats, and provide practical guidance for managing this instinct in ways that respect your cat’s nature while addressing your legitimate concerns about wildlife, hygiene, and those heart-stopping moments when you discover another “present.”

How Evolution Shaped Your Cat’s Hunting Behavior

To truly understand why cats bring dead mice home, we need to appreciate the remarkable evolutionary journey that created the perfect predator sleeping on your couch.

The evolutionary history of feline hunting stretches back millions of years to ancient cat ancestors who developed specialized adaptations for hunting small prey. Unlike pack-hunting predators like wolves, cats evolved as solitary hunters targeting prey smaller than themselves—primarily rodents, birds, and small reptiles. This solitary hunting strategy required different skills than pack hunting, leading to the development of stealth, patience, explosive speed over short distances, and precise killing techniques that minimize energy expenditure.

Domestication’s remarkably limited impact on hunting instincts sets cats apart from most other domesticated animals. While humans have selectively bred cats for temperament, appearance, and social tolerance, we’ve never bred them specifically not to hunt. The reason is simple: for most of human history, we wanted cats to hunt. Ancient Egyptians domesticated cats specifically for their mouse-catching abilities to protect grain stores. Medieval Europeans valued cats for rodent control. Even today, many people acquire cats partly for their pest management capabilities.

Why well-fed cats still hunt confuses many cat parents who assume their pets hunt from hunger. The reality is that hunting and eating are controlled by separate neural systems in cats. The hunting drive is triggered by movement, prey sounds, and opportunity—not by an empty stomach. A cat who just finished dinner will still chase a mouse because the predatory sequence (stalk, pounce, kill) releases dopamine and provides satisfaction completely independent of nutritional needs.

Prey drive as distinct from hunger drive explains why your overfed house cat will still terrorize toy mice or bring home prey they have no intention of eating. The act of hunting itself—the stalking, the pouncing, the capture—provides neurological rewards that satisfy deep instinctual needs. For cats, hunting is both practical survival skill and recreational activity, mental stimulation and physical exercise, all rolled into one irresistible package.

This evolutionary perspective helps us appreciate that when cats bring prey home, they’re not being malicious, gross, or deliberately trying to upset us. They’re simply doing what millions of years of evolution has programmed them to do, following instincts so deeply ingrained that domestication has barely touched them.

Decoding Your Cat’s “Gift-Giving” Behavior

The behavior of cat bringing dead animals home serves multiple purposes in feline psychology and social structure. Understanding these five main motivations helps us appreciate the complexity behind what seems like a simple (if unpleasant) action.

The Maternal Teaching Instinct

Mother cats teaching kittens to hunt follows a predictable progression that provides crucial insight into why your cat might be bringing you prey. In the wild, mother cats begin bringing dead prey to kittens around 4-5 weeks of age, allowing kittens to practice eating solid food. Around 6-7 weeks, mothers bring live but injured prey, letting kittens practice killing techniques in safe conditions. By 8-12 weeks, mothers bring live, healthy prey and demonstrate complete hunting sequences.

Why cats view humans as incompetent hunters stems from their observation that we never successfully catch prey (from their perspective). We can’t pounce on mice, we show no interest in birds, and we certainly don’t demonstrate proper hunting techniques. To a cat, this makes us pitifully unskilled hunters who need education—much like clumsy kittens who must be taught basic survival skills.

Bringing disabled or dead prey as lessons represents the first stage of hunting education in the feline teaching curriculum. Your cat isn’t necessarily trying to feed you (though that may be part of it)—they’re potentially trying to teach you what prey looks like, how it smells, and what you should be pursuing. The fact that you show no interest in consuming or practicing with these teaching aids likely frustrates your well-meaning instructor.

Progressive teaching behavior means some cats escalate their teaching efforts. If bringing dead mice doesn’t seem to improve your hunting skills, they might try live prey next—giving you an “easier” opportunity to practice your capture techniques. The increasingly dramatic nature of some cats’ prey presentations might reflect their growing concern about their human’s survival capabilities.

Gender differences in teaching behavior show that female cats, particularly those who’ve had kittens, display stronger teaching behaviors than males. Spayed females retain these maternal instincts and may redirect them toward their human families, explaining why some female cats are more persistent prey-bringers than their male counterparts.

Providing for the Family Unit

Natural colony behavior in wild cats involves sharing resources and provisioning vulnerable colony members. While cats are solitary hunters, many feline species maintain loose social groups where successful hunters share prey with nursing mothers, injured cats, or young adults still developing their skills.

Viewing your home as safe territory means your cat considers it an appropriate location for storing and sharing resources. In the feline mind, home represents the den or colony center—the safest place to bring valuable resources. The fact that you live there makes it even more logical (from a cat’s perspective) to bring food contributions to this shared space.

Instinct to provision less capable family members explains why cats might specifically seek you out to present prey. If your cat views you as part of their family unit and has assessed you as a poor hunter (see previous section), their instinct to care for family members drives them to compensate for your inadequate hunting skills by sharing their surplus.

Why indoor spaces feel like den locations relates to how cats conceptualize territory. Indoor spaces that are safe, comfortable, and free from threats represent ideal locations for storing food, raising young, and gathering as a social group. Your cat bringing mice inside is actually a compliment—they trust your shared home enough to store valuable resources there.

Connection to kitten-rearing behaviors shows that prey-bringing often intensifies in cats who have raised litters, suggesting the behavior is partly rooted in parental care instincts that persist even after kittens are gone or in cats who’ve never had offspring but retain the instinct.

Pride and Social Status Display

Cats seeking recognition for achievements might sound anthropomorphic, but behavioral research suggests cats do experience satisfaction from successful hunts and appear to value positive attention from their human family members. While cats aren’t motivated by approval in the same way dogs are, they do respond positively to attention and may learn that prey presentation reliably generates human interaction.

Natural inclination to display successful hunts exists in many predator species. Lions drag kills into trees, foxes cache prey prominently, and wild cats in some species bring prey to prominent locations within their territory. This display behavior may serve multiple purposes: deterring competitors, attracting mates, and reinforcing territorial claims.

Attention-seeking through prey presentation develops when cats learn that bringing prey generates guaranteed human attention—even if that attention involves shrieking, jumping around, and animated gestures. To a cat, excited human behavior might be interpreted as impressed enthusiasm rather than horror, reinforcing the prey-bringing behavior.

Individual personality factors mean some cats are simply more inclined to show off than others. Confident, social cats who enjoy human interaction are more likely to present prey prominently and wait for your reaction, while independent or shy cats may quietly cache prey in corners without seeking acknowledgment.

Your Home as a Secure Cache

Food caching behavior in wild felines involves storing excess prey for later consumption. Many wild cat species bury prey, drag it into secure locations, or return repeatedly to cached food over several days. This survival strategy ensures that a lucky hunting day can provide sustenance through less successful periods.

Bringing prey to the safest available location explains why cats specifically bring prey indoors rather than leaving it where they caught it. Your home offers protection from scavengers, other predators, and weather—all factors that could compromise a food cache in outdoor locations.

Protection from scavengers and competitors motivates much food-caching behavior. A mouse left outside might be stolen by other cats, raccoons, birds, or other predators. A mouse brought inside is safe from competitors, ensuring your cat can return to consume it at leisure.

Intention to consume later means not every prey delivery is a gift—some are simply your cat’s meal prep for later consumption. The fact that you remove and dispose of these cached prey items before your cat can return to eat them might explain why some cats seem frustrated or confused when their stored food mysteriously disappears.

Indoor vs. outdoor territory perception varies among cats. Some view their entire home as their territory, while others consider specific rooms or areas as their core territory. Prey is most likely to be deposited in areas your cat considers the safest, most central part of their territory—which might be your bedroom, the kitchen, or wherever they feel most secure.

When Hunting Becomes Recreation

Hunting for mental and physical stimulation occurs even when cats aren’t hungry and have no intention of eating what they catch. The hunting sequence itself—stalking, pouncing, capturing—releases dopamine and provides the same kind of satisfaction that humans get from completing challenging tasks or engaging in absorbing hobbies.

Play behavior extending to live prey can be disturbing to watch but is entirely natural from a feline perspective. Young cats in particular often “play” with prey in ways that hone their hunting skills while providing entertainment. This isn’t cruelty—cats lack the emotional framework to understand prey suffering in the way humans do.

Lack of intention to eat caught prey is common, particularly in well-fed domestic cats. They may go through the entire hunting sequence purely for the enjoyment and stimulation it provides, then lose interest once the prey stops moving. These cats often bring prey home simply because they’re carrying their “toy” back to their territory and don’t know what else to do with it.

Bringing toys home for entertainment might be the most mundane explanation—your cat simply brought an interesting object back to their living space, much like a child bringing rocks or sticks home from the playground. The fact that the “toy” is deceased wildlife doesn’t change the basic impulse to transport interesting items to your home base.

Indoor cat enrichment connections show that cats who receive adequate hunting-simulation play indoors often show reduced prey-bringing behavior when they do go outside, suggesting that satisfying the hunting drive through appropriate play can somewhat reduce (though not eliminate) hunting of wildlife.

What Happens in Your Cat’s Brain During Hunting

Understanding the neurological rewards of hunting behavior helps explain why this instinct is so powerful and persistent even in cats who’ve never needed to hunt for survival.

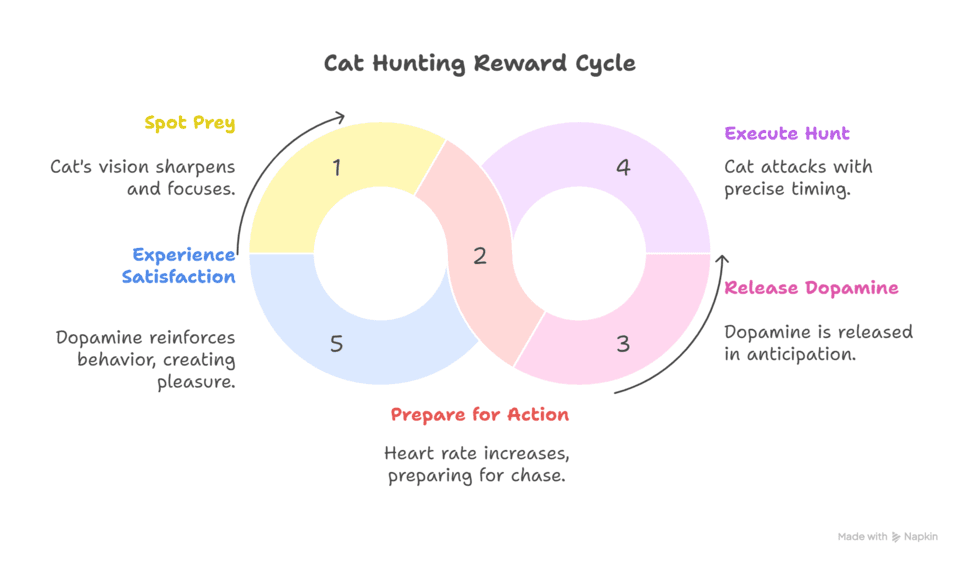

The moment a cat spots potential prey, their brain undergoes dramatic changes. Vision sharpens and focuses on the target, heart rate increases, preparing for explosive action, dopamine begins releasing in anticipation of the chase, and time perception may alter, allowing for precise timing of attacks. This neurological cascade is intensely pleasurable for cats—hunting literally feels good at a biological level.

Dopamine and predatory satisfaction create a reward cycle similar to what humans experience during exercise, completing goals, or engaging in absorbing activities. Each successful hunt releases dopamine, reinforcing the behavior and making cats want to hunt more. This is why cats often seem energized and pleased after successful hunts—they’ve just experienced a natural neurological reward.

Distinction between hunger and hunting drives becomes clear when we observe well-fed cats hunting with enthusiasm equal to or greater than hungry cats. Hunger activates feeding motivation centered in the hypothalamus, while hunting behavior is driven by the prey drive originating in different neural circuits. These systems can operate independently, which is why a satiated cat will still hunt.

Why hunting persists despite domestication relates to the strength and survival value of these neural pathways. In wild populations, cats who lacked strong hunting drives died out, while those with powerful prey drives survived to reproduce. Thousands of generations of selection for hunting ability created neural pathways so robust that a few thousand years of domestication haven’t significantly weakened them.

Breed differences in prey drive intensity do exist, with some breeds showing stronger hunting instincts than others. Oriental breeds, Abyssinians, and domestic shorthairs tend toward high prey drives, while Persians, Ragdolls, and some other breeds show less intense hunting interest—though individual variation within breeds is significant.

The Right (and Wrong) Ways to Handle “Gifts”

When confronted with prey delivery, your response matters both for your relationship with your cat and for managing future behavior.

Why punishment doesn’t work should be obvious given what we now understand about hunting instincts—you’re essentially punishing your cat for being a cat. Yelling, swatting, or other punishment confuses cats, damages your bond, creates fear without understanding, and does nothing to address the underlying instinct. Your cat cannot comprehend why you’re upset about behavior that feels completely natural and even socially beneficial to them.

Appropriate responses that maintain your relationship while addressing the situation include calmly acknowledging your cat (they did work hard, after all), gently removing the prey without drama, redirecting your cat’s attention to play or food, and quietly disposing of the prey where your cat can’t retrieve it.

Safe disposal methods involve using gloves or plastic bags to handle prey, sealing prey in plastic bags before trash disposal, and washing hands thoroughly afterward. Never allow your cat to see you throw away their prey if possible, as this may prompt them to bring more (thinking you lost it) or become protective of future prey.

What to do with live prey brought indoors requires quick action: contain your cat in another room immediately, carefully capture the prey using towels or containers, release the prey outside away from your home (if uninjured), or contact wildlife rehabilitation if the prey is injured. Never try to capture live prey while your cat is present—this becomes a competitive situation that can escalate your cat’s prey drive.

Disease and parasite concerns from prey include toxoplasmosis from infected rodents, parasites like fleas and ticks, bacterial infections from bites or scratches, and potential exposure to rodenticides if prey has consumed poison. Regular veterinary check-ups, parasite prevention, and keeping your cat’s vaccinations current help minimize these risks.

Reducing Prey Kills Without Suppressing Instincts

For cat parents concerned about wildlife impact, several strategies can reduce hunting success while respecting your cat’s natural behaviors.

Bell collar effectiveness and limitations produce mixed results. Single bells can reduce bird catches by 30-40% by warning prey of approaching cats, but effectiveness diminishes as cats learn to move without ringing bells. Multiple bells or specific frequencies work better than single bells, though determined hunters often adapt. Bells are most effective against birds, less so against mice and other ground prey.

BirdsBeSafe and similar deterrent collars use bright colors that make cats more visible to prey, particularly birds. Research shows these colorful collar covers can reduce bird catches by up to 54% when worn during breeding seasons. These collars work on visibility rather than sound, making them effective even for stealthy cats who’ve learned to silence bells.

Feeding schedules and hunting correlation show weak connections—hunger doesn’t significantly drive hunting behavior, so feeding more or less doesn’t dramatically impact hunting. However, regular meal schedules may keep cats indoors during peak hunting hours (dawn and dusk), indirectly reducing hunting opportunities.

Exercise and enrichment as hunting outlets help satisfy prey drive through appropriate channels. Daily interactive play sessions with wand toys, puzzle feeders that simulate hunting for food, fetch games with prey-like toys, and automated laser toys can provide hunting simulation that reduces (but doesn’t eliminate) outdoor hunting motivation.

Indoor time management during peak hunting hours offers the most effective reduction in wildlife impact. Keeping cats indoors during dawn and dusk (when both cats and prey are most active) can reduce prey kills by 50% or more while still allowing outdoor access during safer times.

Catio and enclosed outdoor space solutions provide the ideal compromise: cats get outdoor stimulation, fresh air, and environmental enrichment without access to wildlife. Well-designed catios include climbing structures, perches with views of wildlife, secure screening preventing escapes or wildlife entry, and enrichment items like grass, plants, and hiding spots.

Satisfying Prey Drive Without Real Hunting

For cats who can’t go outdoors or whose hunting needs reduction, providing appropriate outlets for hunting instincts is essential for mental health.

Interactive toys that simulate prey movement work best when they trigger natural predatory sequences. Wand toys with feathers or fabric that flutter erratically, motorized toys that move unpredictably across floors, and puzzle toys that make prey-like sounds all engage different aspects of hunting behavior. The key is unpredictability—prey never moves in straight lines or predictable patterns, so the best toys don’t either.

Puzzle feeders engaging hunting sequences transform feeding time into hunting practice by requiring cats to work for their food. Stationary puzzles with hidden compartments, rolling treat dispensers that must be batted around, and snuffle mats hiding scattered kibble all simulate foraging and hunting behaviors while providing mental stimulation.

Scheduled play sessions mimicking hunting should follow the natural predatory sequence: searching and stalking (slowly moving toys, hiding them behind furniture), the chase (faster toy movement triggering running and pouncing), capture and kill (allowing your cat to catch and hold the toy), and post-hunt calm (ending play with a small treat and grooming time). This complete sequence provides neurological satisfaction similar to real hunting.

Technology solutions for busy cat parents include automatic laser toys programmed to activate on schedules, robotic toys that move randomly throughout the day, and app-controlled toys you can operate remotely. While these don’t replace interactive human play, they provide supplemental hunting simulation.

Balancing Cat Welfare with Environmental Impact

The question of outdoor cat access involves balancing animal welfare, personal freedom, and environmental responsibility—a topic that generates strong emotions on all sides.

Statistics on cat predation impact reveal concerning numbers. Studies estimate that free-roaming cats in the United States kill 1.3-4 billion birds and 6.3-22.3 billion mammals annually, with owned outdoor cats contributing about 30% of these kills. Some bird species face significant population pressure from cat predation, particularly ground-nesting birds and species already stressed by habitat loss.

Ethical considerations require weighing competing values: cats’ welfare benefits from outdoor access (environmental enrichment, exercise, mental stimulation), wildlife conservation interests favor keeping cats indoors, and personal freedom arguments support cat owners’ right to allow outdoor access. There are no easy answers, but informed decision-making requires acknowledging all perspectives.

Compromise solutions exist between full outdoor access and complete confinement: supervised outdoor time on leashes or in enclosed yards, catios providing outdoor experience without wildlife access, indoor time during peak hunting hours (dawn/dusk), and seasonal restrictions during bird nesting season.

Responsible outdoor cat ownership involves keeping cats indoors at night when they’re most effective hunters, using deterrent collars during vulnerable wildlife seasons, maintaining spay/neuter status to prevent contributing to feral populations, and providing identification (microchips, collars) to aid return if lost.

Conclusion

Understanding why cats bring dead mice home transforms this behavior from disgusting mystery to fascinating window into feline psychology and evolution. Whether your cat is teaching you to hunt, providing for the family, showing off their skills, caching food for later, or simply bringing home their recreational kills, they’re following instincts millions of years old that domestication has barely touched. Rather than viewing prey-bringing as a character flaw to eliminate, we can appreciate it as evidence of the remarkable predator sharing our homes while taking reasonable steps to manage behavior in ways that work for both cats and the humans who love them.

The key is finding balance—respecting your cat’s natural instincts while addressing legitimate concerns about wildlife, hygiene, and household harmony. With understanding, patience, and appropriate management strategies, you can honor your cat’s heritage as a skilled hunter while maintaining the comfortable, prey-free home environment you prefer.

Also Read - 10 Cat Safe Air Purifying Plants for Your Home

FAQs About Why Cats Bring Dead Mice Home

Should I praise my cat when they bring me dead mice?

Mild, calm acknowledgment without excessive enthusiasm works best. Say “thank you” quietly and remove the prey calmly without drama. Excessive praise may encourage more prey-bringing, while punishment damages your relationship. The goal is neutral acceptance that neither strongly reinforces nor punishes natural behavior.

Do indoor-only cats have the same hunting instincts?

Yes, indoor cats retain full hunting instincts even without outdoor exposure. They redirect these drives toward toys, household objects, or even your feet under blankets. Providing appropriate hunting simulation through play is essential for indoor cats’ mental health.

Why does my cat bring prey to my bed specifically?

Your bedroom represents your cat’s core safe territory where you sleep (are most vulnerable) and spend significant time. It’s the most secure, central location they know, making it ideal for storing valuable resources or presenting important items to you.

Is it true that female cats bring more prey than males?

Generally yes, particularly spayed females who’ve had litters. Maternal provisioning instincts drive female cats to bring prey home more frequently than males. However, individual variation exists, and some male cats are prolific prey-bringers.

How can I stop my cat from hunting without harming our relationship?

You can’t completely eliminate hunting instinct, but you can reduce kills through deterrent collars, limiting outdoor time during peak hunting hours, providing enrichment and play, and using enclosed outdoor spaces (catios) instead of free-roaming access.

What diseases can cats get from hunting mice and birds?

Risks include toxoplasmosis, parasites (fleas, ticks, worms), bacterial infections from bites, and exposure to rodenticides if prey consumed poison. Regular vet checkups, current vaccinations, and parasite prevention minimize these risks.

Why does my cat meow loudly when bringing prey home?

This vocalization may announce their successful hunt, call you to witness their achievement, mimic the chirping sounds mother cats make when bringing prey to kittens, or express excitement about their catch. It’s a normal part of prey-bringing behavior.

Do cats actually eat the mice they catch?

Some cats eat prey regularly, others never do. Well-fed domestic cats often hunt purely for sport and stimulation without eating what they catch. Cats more likely to consume prey include those with outdoor backgrounds, cats fed raw or meat-heavy diets, and truly hungry cats.

Can hunting behavior be trained out of cats?

No, hunting is an instinctual behavior too deeply ingrained to eliminate through training. You can manage when and where cats hunt and provide alternative outlets, but the drive itself persists throughout a cat’s life regardless of training efforts.

What does it mean if my cat brings live prey vs. dead prey?

Live prey may indicate teaching behavior (giving you practice opportunities), incomplete hunting sequence (caught but not killed), or bringing prey home as a “toy” for entertainment. Dead prey typically represents completed hunts brought home for caching or gifting purposes.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.